About Us

History of TASCC

TASCC was first launched in 2011. It was developed for service providers working with high risk youth, such as those street-involved. TASCC was relaunched in 2016 to contain information for parents and service providers of youth with disabilities. In 2020, TASCC was redesigned with information for youth with disabilities. It also includes accessibility features and a learning management system, with online courses. TASCC was made possible through funding by the Maternal Newborn Child and Youth (MNCY) Strategic Clinical NetworkTM (SCNTM) and PolicyWise for Children & Families.

Purpose of TASCC

The purpose of TASCC is to provide a venue for youth, parents and service providers to access current resources and information that reflects best practice in sexual health education and promotion. TASCC offers practical tools and strategies for high risk youth and youth with disabilities. TASCC is a platform for online learning, a vehicle for knowledge transfer, and a sexual health resource for parents, service providers, and youth.

Why develop TASCC?

Sexuality is an important part of the overall wellness of all people. Although all Canadians have a right to sexuality education not all people receive it.

Youth with disabilities who do not receive sexuality education that is inclusive to their needs, are vulnerable to abuse, sexual exploitation, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, social isolation, and lower quality of life.1

In a study of parents and service providers of youth with disabilities, participants stated education opportunities and resources (e.g., interactive activities, games) are needed to support youth in their learning about sexuality.2

Definitions

Throughout this website, you will see various terms. Here we provide some definitions of those terms:

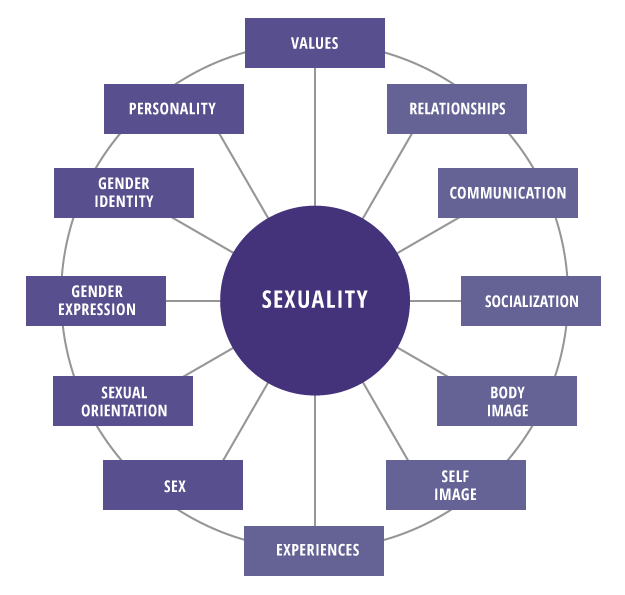

The Sexuality Wheel

The Sexuality Wheel shows how broad the concept of sexuality really is. Each spoke of the wheel represents one part of who we are, all connected and influenced by each other. The spokes on the left show who we are by nature. The ones on the right show who we are taught to be. When all of the wheel’s spokes are in good shape, the wheel moves freely and smoothly; when all parts of our self are healthy, our sexuality is healthy.

Values

A set of ideas that people see as most important, a set of assumptions of how things are. Healthy sexuality is about consistency/congruence between values and actions.

Relationships

The way people are connected and how they act to each other. The ability to have healthy relationships in general can translate into the ability to have healthy sexual relationships.

Experiences

What people have done, gone through, or been exposed to may be understood differently by different people. Personal experience forms the basis for values.

Personality

Qualities that make a person’s character uniquely theirs. Personality is the filter through which other aspects of a person’s sexuality filters through.

Gender Identity

A person’s internal sense of identity as female, male, both or something else, regardless of sex assigned at birth.

Communication

How people connect and share information. Healthy communication is critical to sharing goals and ideas, setting boundaries and limits, and creating understanding.

Gender Expression

How a person presents their gender. This can include appearance, name pronoun, behaviour, voice or body characteristics.

Socialization

Learned behavior including culture, norms and behaviours that are acceptable to society.

Sexual Orientation

A person’s emotional and/or sexual attraction to others. It can be fluid and may or may not reflect sexual behaviors.

Body Image

The image a person has of their own body and how they feel about it. A positive body image often leads to healthier personal decisions.

Sex

Categories (male, female) to which people are typically assigned at birth based on physical characteristics.

Self Image

What a person thinks of who they are. When a person has confidence and comfort with themselves, their bodies, other people and sex, they are more likely to have healthy sexuality overall.

Theoretical Models

The three main models used to inform this website are the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model, the Population Health Promotion Model, and the principles of primary health care.

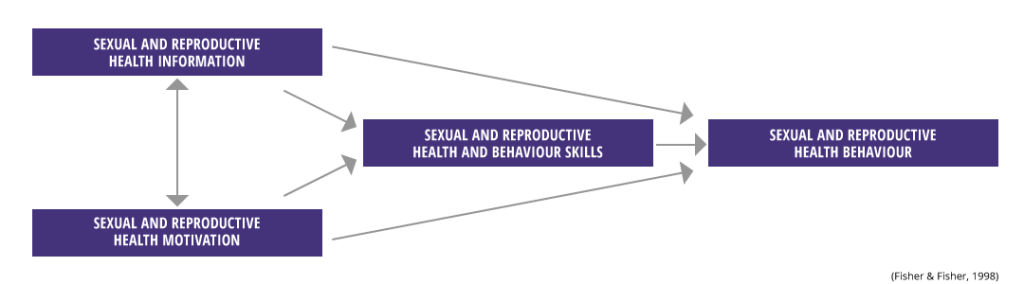

The IMB model proposes that information regarding sexual health, motivation to take action on this information, and behavioral skills for taking action are essential influencers of the initiation and maintenance of “healthy” behaviors. According to the model,8 an “individual’s information and motivation work primarily through [their] behavior skills to affect behavior.”

The IMB model suggests that pertinent, practical, age and developmentally appropriate information that is relevant to the life circumstances of an individual is needed for implementing and maintaining healthy sexual practices.8

The IMB model affirms that motivation to take action on healthy behaviors rests upon three factors: personal, emotional and social motivation. The first factor, personal motivation, is the attitudes and beliefs one holds related to healthy behaviors. The second factor, emotional motivation, is the positive and negative emotions related to healthy behaviors. The third factor, social motivation, is the beliefs regarding social norms or social support for healthy behaviors.8

Although applicable information and motivational aspects are significant components in the adoption of healthy behaviors, possessing appropriate behavior skills is needed to ensure healthy behaviors actually occur. Behavior skills consist of both objective abilities to induce healthy behaviors (e.g., correct condom use) and the self-efficacy for implementing those behaviors.8

For additional information on the IMB model and how to apply it, see The Canadian Guidelines for Sexual Health Education: http://sieccan.org/sexual-health-education/

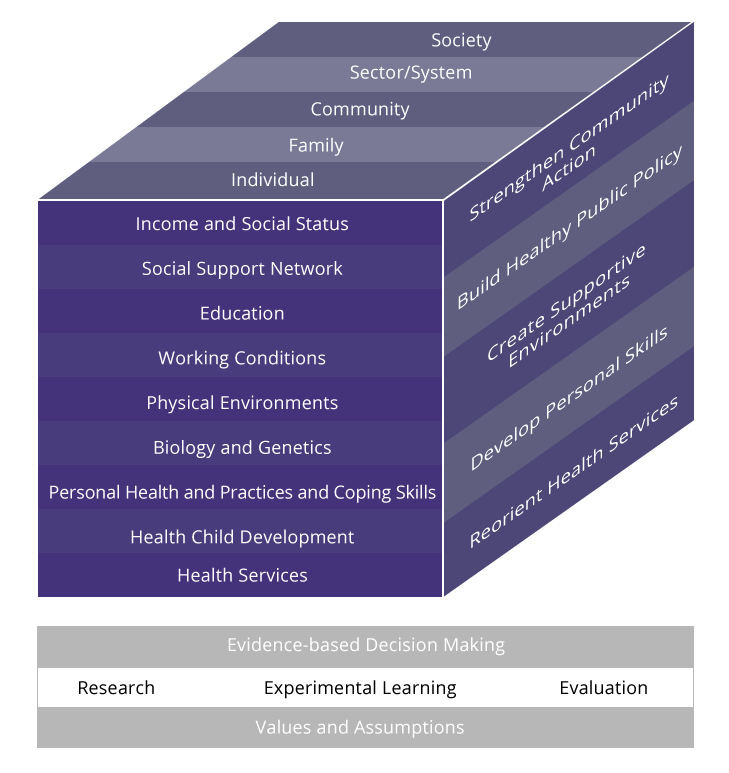

Health promotion is commonly defined as a process for enabling people to take control over and improve their health. Population Health Promotion explains the relationship between population health and health promotion.

It shows how a population health approach can be implemented through action on the full range of health determinants by means of health promotion strategies. Action needs to be taken on the full range of health determinants which include: income and social status, social support networks, education, working conditions, physical environments, biology and genetics, personal health practices and coping skills, healthy child development, health services, gender, and culture. 9

A comprehensive set of action strategies needs to be used to bring about the necessary changes. Action needs to be taken at various levels of society in order for change to be effective and accomplished. 9

For more information on the Population Health Promotion Model, see: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/population-health-promotion-integrated-model-population-health-health-promotion/developing-population-health-promotion-model.html

“essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination”

There are five principles of primary health care:

- Health promotion and disease/illness prevention.

- The use of appropriate knowledge, skills, resources, and technology.

- Individual and community participation.

- Accessible health services.

- Partnerships with various disciplines and sectors.

These principles are at the heart of public health practice and paramount to promoting the sexual health of high risk groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank PolicyWise for Children and Families for funding this website as part of two research projects. We also thank the Maternal Newborn Child and Youth (MNCY) Strategic Clinical NetworkTM (SCNTM) for funding this website as part of a quality improvement project.

We also thank:

-

The service providers and parents who shared their perspectives regarding the information they need in order to better support their youth.

-

The service providers from the PREP Program, Janus Academy and New Heights School who supported this project.

-

The sexual and reproductive health promotion specialists, nurses and community educators with Alberta Health Services Sexual & Reproductive Health (Calgary Zone) for their commitment and hard work in preparing the content for this web site.

-

The parents/guardians, educators, public health nurses, and other service providers who focus tested the website and provided their feedback.

-

The Faculty of Nursing at the University of Calgary for guidance and support of this project. We would particularly like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Sandra Reilly.

-

Creative Elements Consulting Inc. for their creativity. Their contribution on the website design and accessibility features made our website vision become a reality.